The New Orleans Saints have won the Super Bowl and I feel my father's tender presence full inside my heart.

I was 8 years old when the Saints played their first season in 1966. My father was 43, almost a decade younger than I am now. I remember how excited he was, for this put an NFL team just 100 miles down the road from Hattiesburg, in the city where he completed his medical school residency, the city where his first child, my sister Carol, was born.

The first play of that first season made all things good seem possible: a 94 yard touchdown return on the opening kickoff. I imagine it was a brief but glorious light for him during a time when his country was shifting in a way he must have struggled to understand. I remember attending a Saints game with him around 1970 and being scared when everybody would begin to stomp their feet on the metal frame of Tulane Stadium. It was there in 1971 that Tom Dempsey, born without toes on his right foot, kicked a 63 yard field goal, a record unsurpassed to this day.

In 1966, Mississippi felt the world closing in around it, and football steadied its besieged heart. I remember taking trips to Jackson or Oxford on fall weekends to watch the Ole Miss Rebels play. We would tie a rebel flag to the car antenna and wave to the other similarly adorned fans on the highway. It was exciting, yet I remember how that flag would be ragged by the time our trip ended, as its threads were slowly whisked away in the wind. The metaphor seems quite poignant to me right now.

Archie Manning was the Rebel quarterback, and he "sure was something". Folks thought he deserved to win the Heisman trophy but suspected that he wasn't getting sufficient recognition because of the nation's view of Mississippi at the time. I remember repeatedly playing the 45 RPM record of The Battle Of Archie Who" which claimed that "Archie 'Super' Manning could run for President".

When Archie was drafted by the 1971 Saints in the first round, my father had great hopes for his team which hadn't yet compiled a winning season. Unfortunately, this was just one of the many dreams that slipped away from him during his life, for the Saints never won more games than they lost until 1987, 16 years later. I bet my father watched hundreds of those games. I remember endless Sunday afternoons when he would be sitting in his "easy chair" watching his beloved, beleaguered team. I'm sure he dearly wanted me to watch with him, and I tried a few times but quickly grew tired of the endless back-and-forth that never ended well. I could get that at the kitchen table every night.

I attended Tulane from 1976 to 1980. Tulane "Sugar Bowl" Stadium, where the Saints had played all their home games, stood empty during most of those years, since the team vacated when the Super Dome opened in 1975. I went downtown to a few of those games, but the Saints were dull and I was wild, so the team my father loved held no sway for me. In 1980, the year I graduated, the old stadium was demolished.

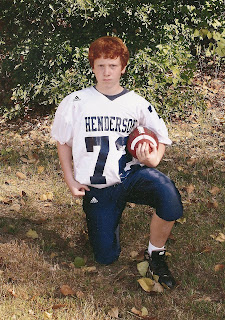

My father died of a heart attack in 1997, sitting in the same easy chair that held him through all those games. He only had the briefest opportunity to know my son Lincoln. Last year Lincoln was selected as his middle school's All-County football player, and I longed for my father's witness to this remarkable achievement. When Lincoln followed this pinnacle by saying he didn't really like the game and preferred to play in the band, I was unexpectedly both surprised and relieved. I wanted him to be more than a football hero.

Tonight I watched, standing with trepidation,, as Peyton Manning, Archie's son, donned a Colts uniform and tried with everything he had to defeat the team that denied his father greatness a generation ago. Just a few minutes ago the Saints defeated the Indianapolis Colts to become Super Bowl champions. And this time I am the one who wanted his son to sit and watch and cheer with his father, just as I am the one who sighed in loving acceptance that he was not about to do this: "tell me in the morning who won, Dad."

So sitting by myself with my loving dog by my side, I cried for my father as the final seconds of this most beautiful and gloriously exciting game ticked away. I felt him so fully present in my heart that it was as if he had mustered his spirit to share that space with me for a few precious, affirming moments of almost indescribable joy. Finally, we watched a game together.

Sunday, February 7, 2010

The Saints Win And My Father Smiles

Posted by

Bill Herring

at

9:49 PM

3

comments

![]()

Labels: Athletic-looba, Family-looba, Hattiesburg-a-looba, Personal-looba

Wednesday, December 3, 2008

Double All-County

team this past week, earning his way onto the honorary DeKalb county all-star team. This is a very high honor for him and a testament to his dedication, focus, attitude, academic performance and familial support. In some ways it's an award the whole family shares much the same way we were all responsible several years back for Gina's graduate degree, right down to Casey who was still a toddler at the time.

In addition to my pride in his accomplishment I feel some vindication (which I'm not proud about) for how last year's football season ended for him, which I've never written about until now, so here goes:

You can read past postings to catch up on the adventures of last year's season, especially in the way my role as father continued to adapt and grow. As the season progressed Lincoln's morale began to steadily decline due to the attitude and decisions of his coaches regarding his role on the team. The head coach personally promised me that he would get to carry the ball (something he'd always wanted to do) in the last regular season game, since neither victory or defeat would change the team's post-season standings. Unfortunately the coach did not do what he promised, and Lincoln's spirit was crushed. The next week he missed practice due to the start of the wrestling season and despite the advance notice I gave about this the coach made the decision to bench Lincoln during the first play-off game. Lincoln came to that game fired up and ready to rock and was stunned to be penalized in this manner.

He was devastated and I was furious. When half-time started he came to me and asked what he should do. I told him I would support whatever decision he made. He thought about it a few seconds and then said "I'm done." I nodded, realizing the import of what was happening as I watched a young MAN emerge from the boy in front of me. He walked calmly, directly and unbidden to each coach and extended his hand respectfully and firmly while announcing his immediate departure from the team.

The coaches were "fit to be tied" as the saying goes and stormed over to me simultaneously defending their actions and condemning his. I didn't allow this to continue for long (what good would a continued battle of wills do at this point?) and escorted Lincoln to the car with both our heads held high. I remember we went to Blockbuster and rented a slew of Japanese monster movies to watch together (they're not very good, in case you're interested).

I was emotionally conflicted for months about whether I was enabling a lasting template of what society calls "being a quitter", but I have found that my most abiding feeling has been one of immense pride at the courage and self-esteem he demonstrated in response to the way he was disrespected (I almost wrote "pissed on") by adults who will never be half the man he is proving himself to be.

His team went on to win the league championship without him, so he did not get an opportunity to fully experience the feeling of riding a season all the way to the very top. We've got a team photo from last year that neither of us has expressed an interest in framing. I've had to work hard and not altogether successfully to avoid holding onto a resentment against the coaching staff for the way they handled him. What helped me greatly was simply knowing how toxic such an approach is for me.

I've subsequently looked for and found unintended positive consequences that would not have occurred if this event had not taken place exactly as it unfolded. (So many times in my life I've found that seemingly difficult times revealed hidden meaning as my attitude softened). For instance, this year's personal victory for Lincoln is much sweeter for last year's disappointment. His demonstrated ability to "gut out" an entire season on a losing team while maintaining a perfect grade point average is a resounding rebuke to any implied charge that he is a "quitter". And in retrospect the way he comported himself by walking away from an important game that he cared deeply about brings to my mind Cyrano's grand retort to the charge that giving away his gold was foolish when he proudly responded "but what a gesture!"

So I came to the decision that it was time to finally forgive last year's coach and move on. Almost immediately after I came to this conclusion Lincoln was selected to play trumpet in the all-county middle school honors band. I was surprised but pleased, of course. A few days later he auditioned to determine his seating order in the band and was chosen to be principal trumpet! First chair! Best trumpet in the county! Who IS this man, and how do I deserve him?

Important Addendum as Of December 12th: I'm almost relieved to say that Lincoln did worse than he expected at the All-District level and did not qualify for All-State. Also, he flubbed a solo at the middle school end-of-semester concert and was embarrassed about it. I gave him less than a minute of advice about handling disappointments with dignity and just saying to folks "it wasn't my finest hour" because people may admire you in victory but they will come to respect you by how you handle defeats, even relative ones. I also pointed out that the more goals you ahve for yourself the more often you will not rise to the level of your hopes and expectations. Only a person with no goals is never disappointed in himself. He seemed to shrug it all off like water from a duck's back, which is comforting to see on a number of levels.

Posted by

Bill Herring

at

10:30 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Athletic-looba, Family-looba

Saturday, May 3, 2008

No Runs, No Hits, No Errors -- Just Memories

Lincoln stopped playing youth baseball this season. His commitments to wrestling and off-season football conditioning were so extensive that adding baseball was just too much to consider. Of course I supported his decision, but if I had realized at the time that last summer was his final season I would have paid more attention and savored the waning moments of his relationship with the sport. We truly don't fully appreciate what we have until it's gone.

Lincoln stopped playing youth baseball this season. His commitments to wrestling and off-season football conditioning were so extensive that adding baseball was just too much to consider. Of course I supported his decision, but if I had realized at the time that last summer was his final season I would have paid more attention and savored the waning moments of his relationship with the sport. We truly don't fully appreciate what we have until it's gone.

I can think back to his first year in T-ball -- was he really FIVE years old? I remember his successes and disappointments, the "thrill of victory and the agony of defeat", the batting lessons, the rain-outs, the stolen bases, the big plays, the dropped balls, the experiences at both pitcher and catcher, the teamwork, the never-ending nuances of the game's finer points, my early years coaching, the dreams and fantasies, the conversations and hugs....

There is a wonderful book called "Little League Confidential" that I have bought for several of his coaches over the years, which chronicles the generally crazy and often exhilarating world of youth baseball. At the end the author writes:

Here's what happens in the end: they stop. The kids just....stop playing baseball. They stop, which is a good thing to keep in mind when you're out there on the Little League playing fields.And that about sums it up. As i reflect on the last 7 or so years in baseball I'm actually relieved to find that I'm relieved -- the promise of the game was generally more than the payoff, the hopes were often outweighed by the heartaches, the dreams by the disappointments. He had a better childhood baseball experience than I did, and I'm very grateful for that.

.....I guess I still believe that if I'd insisted Willie live at the batting cage, insisted that he be a pitcher even though he didn't want to be, that he'd be an awfully good baseball player right now, maybe even good enough to...well, never mind. Let it go.

He has baseball in proper perspective. He and the other kids always did; for the adults, particularly the fathers, it has taken longer.

I think I'm finally starting to get it now, starting to understand. So, it really is a game, huh? And if it's not being played for fun, why play at all? To learn values? That's asking a lot of a game. Play for fun and they'll learn the values, I think. Come to think of it, that is a value.

We still play catch in the yard, my son and I. But it's more pleasant now. No more expectation, no judgments, no instruction, no disapproval, no hard feelings. Just a game of catch. He is careful not to throw the ball too hard.

Posted by

Bill Herring

at

1:57 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Athletic-looba, Family-looba

Sunday, March 30, 2008

Coach

I've agreed to help coach my daughter Casey's 2nd-to-4th grade church softball team. I love this league because it emphasizes fun over winning. I know most leagues profess the same principle, but this one means it. We've played two games already and I think we tied the first and won the second, but I couldn't tell you for sure. This is all especially notable since the church's youth sports director is a former Olympics basketball player, Debbie Palmore. A quick web search revealed that at Boston University she accumulated:

I've agreed to help coach my daughter Casey's 2nd-to-4th grade church softball team. I love this league because it emphasizes fun over winning. I know most leagues profess the same principle, but this one means it. We've played two games already and I think we tied the first and won the second, but I couldn't tell you for sure. This is all especially notable since the church's youth sports director is a former Olympics basketball player, Debbie Palmore. A quick web search revealed that at Boston University she accumulated: 22 BU basketball records, including most points, most rebounds, and mosts assists in a career. The only Terrier women's basketball player to have her number retired, she was twice a finalist for the Margaret Wade Trophy as the nation's top collegiate woman's basketball player.

So here I am coaching a team of 8 girls, and it's fun. That doesn't mean that I love every aspect of it. I had to suspend a standing dinner engagement with a good friend to run the weekly practice, for instance. In addition, I'm coaching a small group of kids with a wide range of experience, skill and interest in the game. That's OK, within certain parameters -- but this past week an issue came up that challenged me on a lot of levels.

One of the more talented players on the team arrived late, and it was quickly apparent she didn't have much enthusiasm for being there. First she was too cold, then too hot, then too thirsty, then too tired, etc. etc. While working on fielding drills she paid more attention to the dirt clods around her than the play in front of her, despite my repeated direction to focus on the drill.

After structuring her a second time I told the team that if I had to keep correcting any one player for not paying attention then the whole team was going to have to run. This is an old technique that is used not only by coaches but also teachers and even parents who have more than one child: giving everybody a consequence for the misbehavior of one or two. The very next play she was again dawdling and the ball skittered right past her, so I immediately told all the girls to drop their gloves and line up on the third base line.

I told them to run to the far fence and back. All of them did except the main culprit who walked the last way back. I lined them up again and told them that we would keep this up until everybody ran all the way. This time she sprinted like the wind while I called out to all of them that "team" means everyone works together for each other so that even when you don't want to do something for yourself you do it for your teammates.

She stormed off and hid behind the dugout until her parents came, then ran to her mother to complain about me. I talked to her mother at some length and explained my position and she said she'd have a discussion with her daughter later on. I tried to say a conciliatory word to the player but she would have nothing to do with me.

I was stirred up over this for a little while, worried I'd over-reacted. Later I talked to Gina and she simply asked "if this was a group of boys would you feel so conflicted?" The answer was an immediate "absolutely not!" That's when I gained clarity and realized that I was subjecting myself to a subversive form of sexism. A team of 10 year old boys would be expected to operate at a minimum standard of responding to a coach, so why was I concerned that a group of girls the same age shouldn't be held to the same standard?

This incident helped me see that the effects of gender-based prejudice are subtle and pervasive. I'm not helping a girl by treating her more softly than a boy, just as I don't help a boy by being overly punitive or competition-crazed. And every kid has the right to experience the pride and joy that comes from being part of a disciplined and dependable group of teammates.

The upshot is that she came to the game Saturday full of good cheer and energy. It was like a fever had broken. Her mother said they had a good conversation after the practice. Because of a conflict with a Girl Scout event we only had FIVE players against the other team's full roster, and even against such uneven odds we came out on top (at least, I think so!) Win or lose on the scoreboard, I felt a real victory had taken place.

Posted by

Bill Herring

at

8:16 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Athletic-looba

Monday, February 5, 2007

Good Blog, Sam

Tonight I happened to see my son Lincoln toss a book from his bed to a chair across the room. Without thinking I said "Good throw", to which he immediately replied "Sam." We both laughed and he remarked that he didn't even mean to say the magic phrase, that it just came out of his mouth without thinking. The in-joke here is that around our household variants of the phrase "Good swing, Sam" have come to mean anything done poorly.

"Good swing, Sam" came out of a Little League baseball game when Lincoln was about 8 or 9 years old. Before then, we were like all parents who cheered, coaxed and encouraged our little Lou Gehrig no matter how well or poorly he performed. With each passing year, however, the praise he earns is more realistic.

I'll always be there for him when things go south. When he was 11, he surprised everyone, including himself, by pitching the best ERA on his team through the first four games of the season. Then he suffered a complete meltdown on the mound and had to be relieved after giving up 5 runs in one-third of an inning. I felt so very badly for him, but I also instinctively knew he was experiencing something extremely important in his development toward manhood. After the game, he and I sat on a park bench until long after the last car had left and all the lights had gone out, using his pain to talk about a lot having to do with life.

But at other times he just plain swings poorly. He knows it, I know it, everybody knows it. It just happens, and I think it's a dishonor to lie to him. I just keep quiet. I've spent enough time teaching him how to talk to himself when things start to turn ugly, so he doesn't need my comments crowding his head. But with each passing year, as the players get older and the game starts to turn more competitive, it amazes both of us how many parents continue to blather inane platitudes at their kids.

It was during the spring season of 3rd or 4th grade when one of his teammates would get up to the plate and strike out every time. The only chance he had to get on base was to be hit by a pitch. Each time he came to bat his parents were ready with a never-ending supply of well-intentioned but ultimately meaningless pep talk.

As a prototypical example, when young Sam stands motionless while a hittable ball sails right over the center of the plate for strike one, his parents will almost inevitably call out, "Now you're ready!" If the second pitch sails three feet over his head and he somehow resists the urge to swat at it like a tennis serve his restraint will merit their rousing cheer of "Good eye, Sam!" Once the next pitch settles deep into the catcher's mitt before he fans mightily at it, his parents will enthusiastically crow "GOOD SWING, SAM!!" It's generally only another pitch or two before he is once again trudging back to the dugout, to the fervent applause of exactly two people.

I feel like I am veering dangerously close to making fun of poor Sam, bless his heart, which is not at all what I want to do. Let me be clear: as a kid, I was the Sam on my team. As the saying went, when I was at the plate I couldn't hit the broad side of a barn with the broad side of a barn, and in the field I couldn't catch a cold. I hope Sam went on to find his true glory, for it sure wasn't going to be baseball. I'm glad his parents were supportive enough to cheer him, but I hope they grew wise enough to know when to stop, to take him by the hand and help him find some other endeavor where he could succeed, and to teach him to fail with dignity.

Every youth sports team now gives each player a participation trophy at the end of the season. Lincoln keeps a few that are meaningful to him, but the rest are stored in a box somewhere out in the shed. There is a New Yorker cartoon where a kid comes home dragging in a trophy bigger than he is, bragging to his father, "we lost." I'm glad I have a son who appreciates the difference between praise solidly earned and the overly enthusiastic applause of well-meaning parents who don't know how to help their child find the elusive pearl hidden deep inside pain and failure. They might as well be calling out "we love you, dumpling", and a need to yell that at a game squanders a more important lesson that has precious few opportunities to be taught.

So now, whenever someone at our household tries something and fails miserably, someone else is apt to call out in a friendly manner, "Good swing, Sam." The goal isn't to be cruel. It's to remind each other that abject, unadulturated failure is as inevitable in life as an accidental fart; maybe a little stinky, sometimes embarassing, but ultimately no big deal. The flip side of the equation is that true success merits true praise, and there is never any doubt that it is genuine and well earned, like a ball hit deep over the fence.

Posted by

Bill Herring

at

9:44 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Athletic-looba, Babalooba's Best, Personal-looba